Why Knowing What You Don’t Know Is More Useful Than Being Brilliant

Introduction

In the year 2000, The CEO of Blockbuster had the opportunity to buy Netflix for $50 million.

I know right? What a bargain.

Yet in what you might call the most extreme f*ck up in business history, The Netflix executives were laughed out of the room.

We all know how that one played out, don’t we?

“Knowing what you don’t know is more useful than being brilliant”

Charlie Munger

This article will explain some of Charlie Mungers ideas about life and business, so that you can avoid any blockbuster sized catastrophies in your own persuits.

Charlie Munger: Your favorite investor’s favorite investor

Charlie Munger is known, to the casual observer, as the right-hand man to Warren Buffet. Together, they’ve built Built their investment firm, Berkshire Hathaway, into a 600 billion-dollar company.

In a recent interview with CNBC, Buffet said of his relationship with Munger:

“It’s better to associate with people who are better than you are”

As you start to read about business and entrepreneurship, you quickly get a sense of Charlie Munger’s influence. Big players in silicon valley like Chamath Palihapitiya, Patrick Collison, and Naval Ravikant, all cite Munger’s ideas in various interviews.

“The best mental models I have found came through evolution, game theory, and Charlie Munger. Charlie Munger is Warren Buffett’s partner. Very good investor. He has tons and tons of great mental models.”

Naval

The least exciting investment strategy you ever saw

Munger and Buffet are proponents of value investing, which involves looking for businesses whose stock trades at a relative bargain. They buy these stocks and grow their wealth as the market corrects in their favor.

“yeah no sh*t, don’t a lot of people do that?”

Well in theory, yes. But figuring out what a company is actually worth, irrespective of the stock price is where things become difficult. And you’d be surprised. Most traders often have no idea about the intrinsics of the businesses that they buy shares in.

Munger and Buffet work only within their own circle of competence. They do not trade based on speculation, and they are happy to stand aside and forego any booming opportunity that they don’t completely understand.

A bull market is like sex. It feels best just before it ends

When we think about investing or entrepreneurship, we think of Steve Jobs. We think of the Facebook IPO. we think of Bill Gates and Jack Dorsey and the PayPal mafia.

Or we think about the crypto billionaires, who took a chance on bitcoin when it was still some nerdy underground idea.

What’s less exciting; what we try not to look at, are the heaps of bodies.

All of those high-risk players, trying to get rich or die trying, that died trying.

The 90% of startup founders whose best laid plans meant nothing in the real world.

The investors who placed confident bets, only to realise that they hadn’t accounted for all of the variables.

Be consistently not stupid

When Alphabet (Google) went public, Berkshire Hathaway did not invest.

“The trouble is I saw that Google was skipping past AltaVista, and I then wondered if anybody could skip past Google”

Apple’s IPO was in 1980, and Berkshire did not buy any Apple stock until 2016.

“We will not go into businesses where technology which is way over my head is crucial to the investment decision.”

When cryptocurrency was exploding, Berkshire-Hathaway steered clear.

“It’s really kind of an artificial substitute for gold. And since I never buy any gold, I never buy any bitcoin”

And yet whilst the market as a whole averaged 10% compounded growth, with 92% of active funds not beating the market, Berkshire-Hathaway has averaged returns of 20% since 1970.

The most successful investors of the last 50 years, did not consider themselves in a position to invest with certainty in many of the glaring stock market opportunities of our time.

“It is remarkable how much long-term advantage people like us have gotten by trying to be consistently not stupid, instead of trying to be very intelligent.”

What is going on here? Why are the most successful investors often the most hesitant to capitalize on what seem like great opportunities?

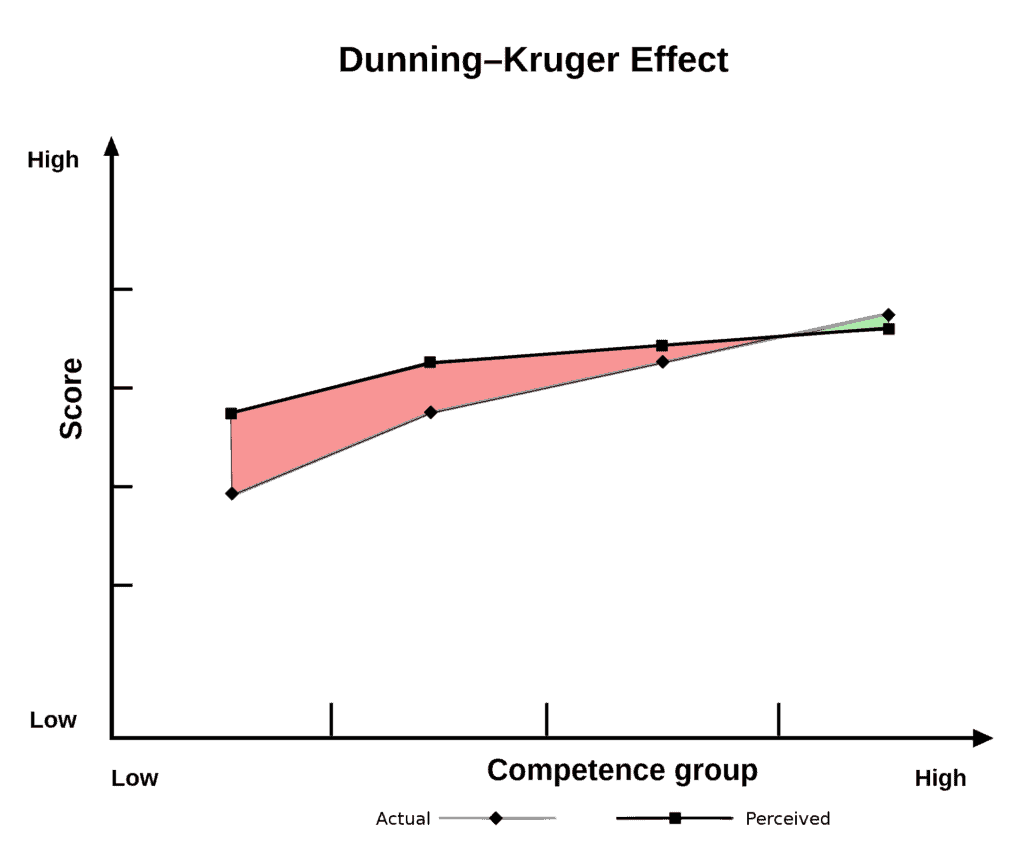

The Dunning Kruger Effect

David Dunning is an American social psychologist, whose research helps to explain this observation.

In his research, Dunning explains that poor performers in many intellectual and social domains suffer meta ignorance- that is, they are ignorant of their own ignorance.

Here’s a graph showing the effect:

If you’ve ever tried to start anything from nothing, I bet you’ve experienced this first hand. To be honest, when I started this blog, it seemed like the world’s easiest business.

Writing articles. How hard can it really be to write articles? Come on, seriously? I’m a professional chef. I didn’t even think this would be real work.

Of course, I was right over to the left on the competence line. The meta ignorance had me feeling completely sure of myself, but over time this faded.

Things look easy until you actually try to do them

You write a few articles that you think are brilliant. You post them to a plain-ass website and feel like you’re absolutely flying.

Then later on, like weeks later on, you learn what keyword research is. You learn how to find out what people are actually searching for online. You learn that, almost certainly, no one will ever see all those first articles you wrote.

So you correct your course and keep working, armed with a little piece of earned wisdom, until one day you realize that you chose a stupid domain.

Or you’ve got slow hosting.

Or your paragraphs are structured all wrong.

Or your design’s trash.

Title choice. Monetization. Niche selection.

All of the elements of a great blog, that you were once blissfully unaware of, start to make themselves known. Each time you learn something useful, you realize how ignorant you once were. As you keep failing and learning, you get more and more comfortable with the idea of your own incomprehension.

When Charlie Munger sees a company on the rise, he doesn’t just jump in. He reads and reads and reads. And if he decides that there are too many unknowns in a business that’s set to explode, He accepts his own limitation and takes his money somewhere else. He doesn’t invest in anything that he doesn’t completely understand.

Sure he’ll miss out on some big winners this way, but he’ll also avoid a whole lot of overhyped losers. And when you’re playing with over $2 billion like Charlie, not losing money is probably right up there alongside getting more of it.

How Brad Jacobs made $3.7 billion across 4 different industries

There are a lot of billionaires out there, but Brad Jacobs stands out as unique. He has founded, over the course of his career, 5 different companies in 4 different industries. All of them, before Jacobs moved on, were worth north of a billion dollars.

Although he maintains a pretty low profile, the My First Million podcast recently detailed Jacobs’ businesses in this episode:

It’s shocking just how different each of Jacobs’s successful ventures is. It is rare for someone who trades oil successfully to go on to dominate waste management, and then equipment rental, and then logistics.

Obviously, with a man like that, there’s a lot to be learned. What I found interesting, was Jacob’s process for identifying potentially profitable industries that he doesn’t know anything about.

“He spends 3 months. He reads tonnes of reports, and then he calls 100 experts in each industry. And he just goes and he sits down with them, and he just asks them questions…He’s this multi-billionaire and he calls these people, and he sits down, and he listens”

You might think that someone with a track record like Jacobs knows an absolute f-ck tonne about business.

Obviously, he knows a f-ck tonne about business.

But he’s out here, interviewing people with a fraction of his own wealth, working to figure out what it is he doesn’t know.

That is, from what I can see, the kind of brilliant humility that the absolute most competent players in business and investing deploy.

Recognize the strength of understanding your weakness

Maybe it’s a bit of a stretch. We were talking about Charlie Munger, and then blogging, and then entrepreneurship. But what ties all of these threads is the value of understanding where you are weak. Knowing what it is that you don’t know.

If you feel completely sure about how things are going to play out, it looks like you might be right over to the left side of the Dunning Kruger graph.

That’s the last place you want to be.

Charlie Munger has shared a lot of gold like this over the years. He is famous for his mental models, which he uses to solve problems and make sense of the world.

Here are 3 of my favorite Charlie Munger principles.

Inversion

In world war 2, Charlie served as a meteorologist. His job was to predict the weather and work out where and when to send out Aeroplanes. His main priority, of course, was keeping American pilots safe.

“I inverted. I said ‘suppose I want to kill a lot of pilots. What would be the easy way to do it?’ and I soon concluded the only easy way to do it would be to get the planes into icing the planes couldn’t handle, or to get the pilot into a place where he’d run out of fuel before he could safely land. I decided I was going to stay miles away from killing pilots. I think that helped me be a better meteorologist in world war 2”

I have since used inversion thinking on a number of occasions. If you figure out all of the ways that something could go wrong, then you can develop a better strategy to make things go right.

The power of incentives

Never, ever think about something else, when you should be thinking about incentives.

“One of my favorite cases about the power of incentives is the Federal Express case. The integrity of the Federal Express system requires that all packages be shifted rapidly among airplanes in one central airport each night. And the system has no integrity for the customers if the night work shift can’t accomplish its assignment fast. And Federal Express had one hell of a time getting the night shift to do the right thing. They tried moral suasion. They tried everything in the world without luck. And, finally, somebody got the happy thought that it was foolish to pay the night shift by the hour when what the employer wanted was not maximized billable hours of employee service but fault-free, rapid performance of a particular task. Maybe, this person thought, if they paid the employees per shift and let all night shift employees go home when all the planes were loaded, the system would work better. And, lo and behold, that solution worked.”

Make friends with the eminent dead

“In my whole life, I have known no wise people (over a broad subject matter area) who didn’t read all the time–none, zero. You’d be amazed at how much Warren reads–and at how much I read. My children laugh at me. They think I’m a book with a couple of legs sticking out.

I am a biography nut myself. And I think when you’re trying to teach the great concepts that work, it helps to tie them into the lives and personalities of the people who developed them. I think you learn economics better if you make Adam Smith your friend. That sounds funny, making friends among the eminent dead, but if you go through life making friends with the eminent dead who had the right ideas, I think it will work better in life and work better in education. It’s way better than just being given the basic concepts.”